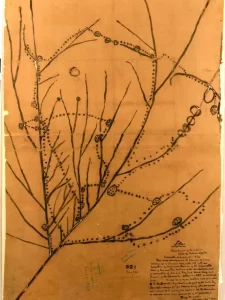

One of the best ways to understand Ioway history is to learn about our treaties and the steady loss of our lands. Once, our Ioway homelands included millions of acres across several states, centered in Iowa. Now, the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska and the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma own just thousands of acres in Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma.

Like many American Indian peoples, the Iowa Tribe lost its lands through a series of treaties. Those treaties are also the legal basis for recognition of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska as a federally-recognized tribe, and its relationship to the U.S. government.

There were 9 treaties between the Iowa Tribe and the United States of America. Through these treaties, a portion of which were fraudulent, and all of which were pressured upon the Ioway under duress, the Ioway lost all of our ancestral homelands in approximately 50 years, from 1809 to 1861.

The Treaty Process

The way the treaty process went was something like this (from the U.S. point of view):

- 1. Establish a legal relationship with the tribe, and exclude it from similar relationships with other countries like Britain or France.

- 2. Establish boundaries between tribes (there were rarely hard-and-fast boundaries between tribes), and try to stop intertribal warfare, much of which was caused by the migration west of tribes being pushed out of their lands by white settlements and wars further east.

- 3. Once the tribal boundaries were fixed and relative peace was made, white squatters began to move in and occupy the best Indian farming areas and to hunt out the wild game.

- 4. Once the best areas were taken by whites and game was scarce, conflicts between the tribes and the squatters was inevitable.

- 5. Establish U.S. Military power and deal with the conflicts by removing the Indians to more distant lands. The Indians sometimes went willingly along at this point because the best areas and the game were taken by the whites. When they didn’t go along, the U.S. Military would use the conflict to force a settlement and removal of the tribe to a more distant area, with promises that this would be the last time of removal.

- 6. Begin the next phase with Step 3 (above), and repeat again and again…

Overview of the 9 Treaties Between the US and the Iowa Tribe

The Final Chapter on Ioway Land Loss

The formation of the Iowa Reservation in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) was established by Presidential Executive Order in 1883, as home for the Southern Ioways, but unknown to them it had a provision that other tribes could be settled on their reservation.

In 1887, the northern Ioway lands on the Great Nemaha Reserve were allotted in severalty (individual land holdings) (24 Stat. 367). The Dawes Severalty (Allotment) Act was also enacted in 1887. Both the northern and southern branches of the Ioway were allotted in 1890, further losing much of their land. Many reservations often look like checkerboards of white and Indian ownership because of the Dawes Act.

In 1891, the remaining tracts of southern Iowa lands that were not allotted were opened to the Oklahoma land rush, or Run of 1891. In 1895, some southern Ioway left the Perkins area to join the Otoe community near Red Rock.

Today, both the Iowa of Kansas-Nebraska and the Iowa of Oklahoma are trying to buy back as much of their former reservation lands as they can, using revenue from tribal enterprises.